How 'Evangelion' opened my eyes to my depression

Until I saw the show in 1997, I didn't know how to describe my feelings.

Author: Gene Park

Source: The Washington Post

Dated: June 27, 2019

Small moments have a way of insisting on themselves, even if you do not choose to remember them, leaving trivial but permanent imprints.

It was 1996 when I sat alone in a dark theater to watch "Fargo." I had no friends who wanted to see it with me. At 15, I felt like I had no friends anyway. The rows were nearly empty, save for a middle-aged couple making out in the darkness.

"How dare they," I thought, grimacing with disapproval. This was a serious movie that demanded a viewer's attention! Yet it was just me, absorbed in the film, before I noticed this couple. My resentment melted into indescribable loneliness, leaving me thinking I was the weird one. There were two of them, one of me. Majority rules. They giggled to each other, I frowned to no one.

Then, a year later, I watched a character on screen go through almost the exact same thing. It was 14-year-old Shinji Ikari, the protagonist of "Neon Genesis Evangelion," the renowned anime TV series that just saw its first global release on Netflix this month.

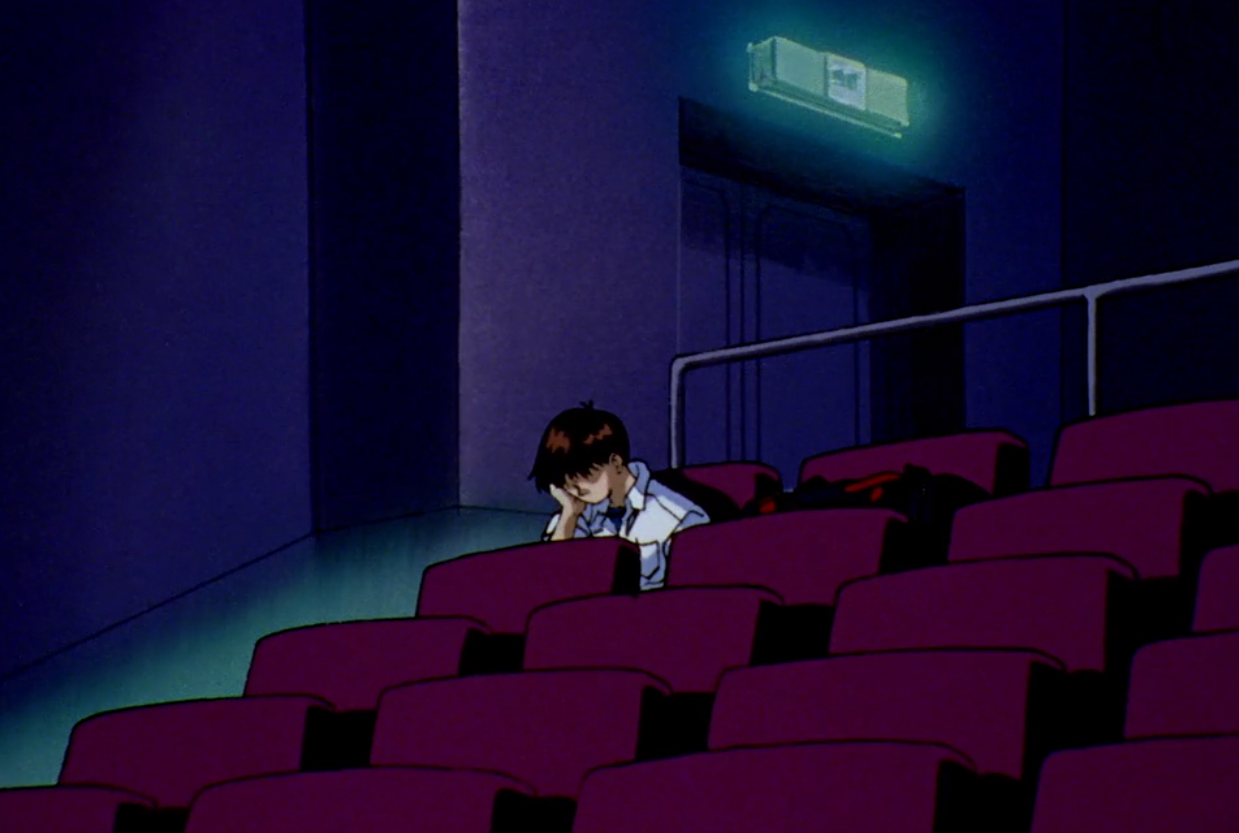

In an early episode, Ikari — who has been forced to pilot a giant robot suit to save humanity — runs away from this unwelcome burden. He sits in public transit, listening to the same songs on repeat, going nowhere fast, ultimately making his way to a theater to ponder his place in life. A couple gets frisky in front of him, and he is immediately overcome with anger and sadness. He moves on to sleep on a public bench. He does not say a word throughout the sequence.

Like my own experience watching "Fargo," this sequence was a small thing — especially in a series that features towering mecha suits battling cosmic angels. Yet, with this brief sequence, a TV show helped me understand something about my own mental health for the first time.

In 1997, when I first saw the show, there was no national conversation about depression. The Internet was still in its infancy, so finding other like-minded people was a challenge. I grew up as an Asian American in the Pacific islands, where these conversations were even less likely.

"Evangelion" creator Hideaki Anno was already 35 when he began discovering his own depression. He created the show after four years of barely leaving his home. Early in his work on the show, he described himself as a "broken man who could do nothing for four years ... one who was simply not dead." His growing awareness spilled into the writing. His mental illness became inseparable from his art.

Shinji's lines below were echoes of the voices in my head.

"I'm worthless. I don't have anything to be proud of."

"They praised me, but I'm not happy."

"You have no identity outside of [your job] don't you?"

Listening to this fictional character's frustrations, I felt — to quote the vernacular — seen.

I had grown up surrounded by people who were, despite their best intentions, just as confused about what to do with me, the boy who stared down at the earth as if it would fall away. For them, being "depressed" was merely a momentary lapse in happiness.

"What have you got to be sad about? Stop being depressed."

"Don't be such a crybaby."

The people around Shinji called him a crybaby, too. They yelled at him to get back in the robot and fight. They all silently nursed their own deep issues, aware of Shinji and each other's pain, yet unable to do anything about it. Watching their struggles, I felt less alone. School taught me about the world. "Evangelion" was teaching me about myself.

Those lessons only became more pronounced as the show lurched and quivered toward its infamously unhinged end, laying bare the tragedy of untreated mental illness. For me, though, it was nearly too late. A year after I saw the show, on the eve of the first day of 1999, I would make my first attempt to take my own life. I was immediately hospitalized and kept in a psychiatric ward against my will for weeks, missing days at school.

I was discharged, and yet despite what I went through, I continued to live heedless and untreated. A momentary lapse in happiness became 19 years of alcoholism and various addictions, where I once again sought dark spaces, feeling less odd thanks to how numb I felt.

Today, I am 37. I have been in regular therapy for the past two years. I began medication for my depression this year. I am sober, and I have quit smoking for several months now. Like Anno writing "Evangelion" in his mid-30s, I am beginning to understand myself better.

Today, thanks to the show's global release, I can revisit its ending with a more seasoned mind and heart, finally ready to internalize its message: that everyone has a right to exist and that the mere act of shared existence with others, no matter how tough that can be, gives you worth.

It is a message that deserves a permanent imprint on my memory. This time, outside the dark theater of my mind, it is one I choose.